Related Article

Related Article

Roux-en-y Gastric Bypass Transcript

Roux-en-y Gastric Bypass

This is Dr. Cal Shipley with a review of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure.

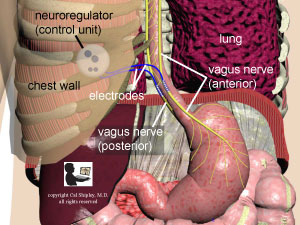

The Roux-en-Y was developed over 20 years ago and today is the most widely performed bariatric surgery procedure in the world, with about 200,000 procedures performed annually. It has become the bariatric surgery procedure of choice because it results in greater weight loss with longer-term results than alternative procedures such as gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, and vagal stimulation, among others.

How the Roux-en-Y Works

The Roux-en-Y works by limiting the volume of food that can be ingested and reducing the absorption of nutrients, and, in addition, as we’ll see in a moment, by eliminating the movement of food through the upper portion of the stomach, also known as the fundus, and the duodenum, located in the upper part of the small intestine.

Hormonal Changes and Satiety

The procedure appears to induce hormonal changes, which increase the feeling of fullness and decrease hunger. I’ll take a closer look at both of these effects later in this presentation.

Roux-en-Y procedure

Laparoscopic Approach

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been performed as a laparoscopic procedure since its inception in the mid-90s. The laparoscopic approach eliminates the need for large, open incisions in the abdomen and relies instead on several very small incisions through which the laparoscopic instruments and camera are passed.

Preoperative Preparation

In preparation for the surgery, no liquids or food are allowed by mouth for at least eight hours prior to the procedure. This is also known as NPO. This ensures that no previously ingested food or excessive gastrointestinal secretions are present in the stomach and small intestine at the time of the surgery.

Partially digested food particles and gastric secretions can cause serious complications if they spill into the abdominal cavity during the surgery. Pre-surgery NPO orders are a standard practice for any patient undergoing a general anesthetic, even if the surgery does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, as a protection against accidental aspiration of stomach contents into the airways and lungs.

As shown, portions of the liver and large intestine also known as the colon lie in front of the stomach, the duodenum and the upper portion of the small intestine, also known as the jejunum.

Abdominal Organ Exposure

Laparoscopic instruments are used to retract the liver and colon away from the operative area. The stomach, duodenum, and jejunum are freed of their attachments so that they may be more easily manipulated.

Roux-en-Y Configuration

The stomach is then divided very close to its top leaving just a small pouch attached to the esophagus. Both ends of the stomach are then closed. The jejunum is then divided and brought up and attached to the stump of the stomach. The unattached (proximal limb) of the jejunum is then reattached to the distal limb lower down as shown. This re-attachment of the jejunum is critical in order to allow bile from the liver, gastric secretions from the stomach, and digestive enzymes from the pancreas to continue to flow. The key components of the procedure have been completed.

Leak Test

Many surgeons routinely perform a leak test either during the surgery, or within 24 hours of the conclusion of the procedure.

The leak test ensures that all of the various intestinal connections and closures of the stomach have been adequately sealed.

The leak tests can be accomplished in a variety of ways including the use of an endoscope, or certain dyes during the procedure, or having the patients swallow a radio-opaque substance such as barium postoperatively.

It is important to note that the performance of the leak test is not mandatory in ensuring a successful postoperative course, and many experienced bariatric surgeons only perform one if the patient’s clinical course is suspicious for a leak.

Postoperative Diet Advancement

Provided the patient is otherwise well on the first day after the surgery, water is given orally in small amounts. If water is well tolerated, the diet is then gradually advanced and the patient discharged on a full liquid diet.

After discharge and depending on patient tolerance, the diet is gradually increased over a two month period, first to a soft diet, and ultimately to solid foods.

Roux-en-Y Results

Now let’s review the physical and physiological effects of the Roux-en-Y procedure.

The new pathway for the flow of food and liquids is as shown. The stomach has been virtually eliminated as a receptacle for food forcing a much-reduced intake. The marked limitation on food intake results in much-decreased nutrient and calorie absorption. As previously mentioned, note that the duodenum and fundus of the stomach are now completely bypassed. The bypassing of these areas appears to lower postoperative levels of hormones such as Leptin and Ghlerin leading to decreased hunger and increased feelings of satiety.

Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y

A final note. In recent years, the sleeve gastrectomy procedure has begun to rival the Roux-en-Y in terms of number of procedures performed annually. Most notably, the Finnish SLEEVEPASS study published in 2018 compared total weight loss after five years in sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y and found no statistical difference.

While sleeve gastrectomy has always been touted as having fewer postoperative complications, other recent studies have shown no difference in complication rates comparing sleeve gastrectomy to Roux-en-Y at five years of follow up. However, whether these comparisons between the sleeve gastrectomy to Roux-en-Y procedures will hold up in the long term is still an open question and will require further study.

You can learn more about bariatric surgery by clicking on the related article link on this page.

Cal Shipley, M.D. copyright 2020