Obesity and Bariatric Surgery

Lately I have been re-reading a fascinating book that I bought a few years ago called “The Clockwork Universe – Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the birth of the Modern World” by Edward Dolnick (HarperCollins 2011). The book focuses on the 17th century, and in particular, on the greatest minds of the day (Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, Christopher Wren, etc.) and how they gave birth to modern science and the scientific method. As background and context, Dolnick starts with a detailed review of 17th century society, including the social, political and living conditions of the time. It was a time when epidemics of Plague swept through cities and nations, leaving millions of dead in its wake. The “Doctors” of the day not only had no effective treatments for the disease, they had no clue whatsoever as to its cause – the role of plague-infected rats, and the fleas who bit them and then transmitted the organisms (Yersinia Pestis) to humans, would not be understood for another two hundred years.

Lately I have been re-reading a fascinating book that I bought a few years ago called “The Clockwork Universe – Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the birth of the Modern World” by Edward Dolnick (HarperCollins 2011). The book focuses on the 17th century, and in particular, on the greatest minds of the day (Isaac Newton, Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, Christopher Wren, etc.) and how they gave birth to modern science and the scientific method. As background and context, Dolnick starts with a detailed review of 17th century society, including the social, political and living conditions of the time. It was a time when epidemics of Plague swept through cities and nations, leaving millions of dead in its wake. The “Doctors” of the day not only had no effective treatments for the disease, they had no clue whatsoever as to its cause – the role of plague-infected rats, and the fleas who bit them and then transmitted the organisms (Yersinia Pestis) to humans, would not be understood for another two hundred years.

Today, medical science has long since appreciated the causes and controls for the Plague (although Bubonic Plague is still present in wild rat populations around the world and occasional human infections still occur http://www.cdc.gov/plague/).

Obesity – Death by Numbers

In the United States, we don’t fear Plague as Europeans did in the 17th century. Instead, we have our own “plague”, and its name is obesity. Obesity doesn’t kill us as quickly as the Plague, but it does so just as certainly, and is capable of causing much human misery along the way (not to mention the costs to Society in lost productivity and health care costs). And because of the relatively slow onset of its damaging effects, we don’t fear obesity like we should. According to an excellent review by the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources http://www.wvdhhr.org/bph/oehp/obesity/mortality.htm, obesity in America is now the second leading preventable cause of death, right there behind our old friend tobacco, and accounts for approximately 300,000-400,000 deaths per year. That’s a lot of people dying each year from a PREVENTABLE condition, and qualifies obesity as a genuine epidemic. The presence of obesity as an independent factor increases death rates among all comers – men and women, blacks and whites, smokers and non smokers, as well as those who have no preexisiting or coexisting diseases, and those who do. Obesity kills primarily by causing cardiovascular disease and cancer. The cardiovascular disease caused by obesity mainly relates to conditions of high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes mellitus, and elevated blood fats (hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia). These conditions, when occurring as a result of obesity, are known as “comorbidities”.

Obesity – Definition

Medical scientists have employed a variety of definitions of obesity through the years, but today the Body Mass Index, or BMI, is thought to be the most useful single measuring stick. The BMI is calculated by taking your weight, and dividing it by the square of your height. Here’s a handy BMI calculator. Most authorities consider a normal BMI to be up to 25, with overweight defined as 25-30, and obesity >30. Obesity is then subdivided into moderate or (Class 1 -BMI 30-35), severe or (Class 2 – BMI 35-40) and very severe (Class 3 – BMI >40). In the WVDHHR review, increased death rates were associated with all BMIs of greater than 25, with increasing numbers of affected individuals correlating with increasing BMI, even the individuals in the “overweight” category (BMI 25-30) were adversely affected. Under these definitions, about 97 million Americans are overweight or obese. While the obesity epidemic is a worldwide phenomenon, the United States has the unfortunate distinction of being the leader in the percentage of its population that is obese, with fully one third of the adult population weighing in with a BMI of 30 or greater.

Obesity – Causes

The cause of weight gain in a human being is pretty straightforward – if the number of calories consumed over time is greater than the number of calories burned by the body, there will be an increase in weight, so it all boils down to calories in versus calories out. The average human has 25-35 billion fat cells. During times of excessive weight gain, this number may increase to up to 150 billion fat cells. Once these fat cells have being created, they do not decrease during a lifetime. Rather, the cells shrink or expand with changes in weight. This is considered to be a major reason that individuals who have experienced significant weight gain, and then have lost weight, have difficulty preventing recurrent weight gain (there is research under way to find drugs that may reduce the total number of fat cells).

We all have voluntary control over the “calories in” part of the equation. There are individuals who are born lacking substances which regulate appetite and normal feelings of satiety in response to food consumption, but these are rare exceptions. The calories out part of the equation is a little trickier. The metabolic rate, that is, the rate that at which a given individual burns calories at rest, or even during exercise, may vary widely from person to person. Moreover, the metabolic rate in most humans tends to decrease with age. As a result, the same exercise routine that maintained a steady weight at age 20, may not do the trick at age 50. This can become particularly problematic for obese individuals who develop musculoskeletal conditions as a result of their obesity. If you are obese, and have arthritic degeneration of the knees, the arthritis may make it difficult to exercise to the level necessary to help you lose weight. As a consequence, you gain more weight, your arthritic condition worsens, and a vicious cycle is established that can be very hard to break. There are diseases, such as hypothyroidism, that can abnormally decrease metabolic rate and cause excessive weight gain and obesity, but again, afflicted individuals are the exception to the rule. Add to all of this the fact that Americans as a population have become increasingly sedentary, and less likely to make exercise part of their daily routines over the past 50 years, and you can see the problem.

Genetics certainly play an important role in the tendency to obesity. Children born of an obese father, or particularly of an obese mother, have a much greater chance of developing obesity by adulthood. But according to the WVDHHR review, the gene pool in the US has not significantly changed in the decades during which the incidence of obesity has skyrocketed. In other words, an individual may be born with a tendency to obesity, but the environment into which he or she is born must be conducive to developing that potential. Scientists refer to this type of environment as “obesogenic” – too much availability of high calorie food, too little encouragement to participate regular physical activity.

Obesity – What to do?

In view of the simplicity of the problem – too many calories in and not enough calories out – the solution for obesity would seem straightforward enough – REDUCE THE CALORIES IN! As the wise man once said, this is easier said than done. Ask anyone who has tried to lose weight. In a society where sugar and fat are in such abundance, can be had in large quantities at such a cheap cost, and are constantly being pushed at us via advertising in print, on TV, and now on the Web, it can be incredibly hard to change the eating habits of a lifetime. Add to that the fact that the “calorie out” part of the equation, meaningful bodily exercise, is strictly an optional activity for most of us, and you begin to understand the depth of the problem.

There are a few lucky, determined souls who simply decide to reduce intake and increase output, and have the willpower and discipline to do it, and stick with it, and to those few I say, congratulations. For the rest of us here in the land of plenty, other avenues must be pursued.

Obesity – Diets

Diet plans and programs to aid the overweight and obese are almost as numerous as the number of days in a decade. “Branded” diet programs, such as the Atkins, the South Beach, Jenny Craig, Weight Watchers, etc. can be divided into 3 basic groups – low fat (ie Ornish), low carbohydrates (ie – Atkins), and “moderate macronutrients” (ie Jenny Craig, Weight Watchers). Low fat and low carb diets restrict fats and carbs respectively, while “moderate macronutrient” diets have a balanced approach to composition with carbs, protein and fats. Bottom line, all of these diet programs attempt to get weight off by working on the “calories in” part of the metabolic equation, that is, by reducing calorie intake. And each program claims to be more effective than all of the others. The September 3rd issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association contains several very interesting papers and editorials on the state of Obesity treatment in America. A study by Johnston et al compared the effectiveness (in terms of amount of weight lost at 6 and 12 months) of 10 of the most popular brand name programs, and came to the conclusion that all of the programs, if adhered to, resulted in weight loss, but that no program was statistically superior to another.

A follow up editorial by Van Horn raises several very important questions aside from the basic issue of how well diet programs work. How sustainable are the various diets – that is, how difficult is it for individuals to stick with the diet over the long term? What is the potential for adverse effects on the body with diets that take an “unbalanced” approach to nutrient intake. For example, does long-term use of a high protein diet result in damage to impairment of kidney function or excessive calcium loss? Are certain essential nutrients limited with deleterious effects? These are all issued that need further study.

My own attitudes toward weight loss programs and diets have been formed through many years of working with overweight patients as a Family Medicine doctor. On the plus side, I appreciate the structure and regulation that diet programs provide for many folks trying to lose, or control, their weight. Many of us just can’t regulate our calorie intake on our own. We need a plan. Give us a plan, and we can follow it.

But my biggest concern regarding diet programs is this: what are they teaching patients about how to eat when they diet is concluded (most people do not adhere to a diet program for life)? What are they teaching patients about the “calorie out” part of the equation (ie-exercise)? I’ve seen so many patients who have successfully lost significant weight while following a program, only to regain the weight once they reached their goal and stopped the diet. There has been some evidence that weight “yo-yoing”, that is, losing and gaining and losing and gaining over time may be as, or even more, dangerous to the physiology than just being overweight, and staying overweight.

The WFPB diet

Much recent scientific evidence indicates the best diet (I prefer to call it a “Liveit”) is a Whole Food Plant Based one. A WFPB intake provides not only a higher concentration of high-value micronutrients (read anti-cancer) than meat, eggs and dairy, but also eliminates the excessive calories and harmful (read cancer promoting) hormones, preservatives, antibiotics, and dyes contained in animal-based foods.

The WFPB diet can be very difficult for most North Americans adhere to, as most of us have become addicted to the meat, salt, fat and sugar we were raised on.

Nevertheless, there are many legitimate scientific studies that support the WFPB liveit, not only for long-term weight loss, but also for reversal of many of the diseases associated with a heavily carnivorous diet.

The medical profession (in my humble opinion) have been very lax in considering diet as a key factor in human disease.

This neglect on the part of physicians is beginning to change, and there are several M.D.s who have been taking the lead in promoting the WFPB lifestyle. Here are a few of the more prominent:

These guys are serious scientists, not “fad diet gurus”. Take a look at their sites- it could change your life…

Obesity – Bariatric surgical treatment

Bariatric weight-loss surgery has been proven to be the most effective treatment for severe obesity in the United States, and is now the second most frequent surgery performed (next to cholecystectomy – gallbladder removal), with 150,000 procedures per year. Currently, the three most popular bariatric procedures, in order, are Roux-En-Y gastric bypass, Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy, and Adjustable Gastric Banding (“Lap Banding”).

Surgical treatment of obesity is not without the possibility of significant risk, and has traditionally been reserved for those individuals in which serious* attempts at diet and lifestyle modification have failed, and in whom the BMI is >40 ( level 3 severe obesity) , or in whom the BMI is 35-39.9 (level 2 moderate obesity) with the presence of an obesity-related comorbidity (ie – diabetes type 2, hypertension, joint problems). These criteria were initially developed by the National Institute of Health, and are based on the notion that mortality rates were directly related to BMI; the higher the BMI, the greater the chance of premature mortality. These same criteria are utilized by almost every bariatric surgery program in the United States, and have been for the past 20 years. In addition, most centers require that potential candidates be non-smokers, or that smokers have quit for a minimum of 6-12 months prior to surgery.

An article by Dimick and Birkmeyer in the previously mentioned September 3rd issue of JAMA questions the wisdom of continuing to use this rather simplistic model for deciding eligibility for bariatric procedures, and suggests instead that, based on more recent evidence, the direct link between BMI alone, and mortality, may not be as strong as previously thought. In particular, studies have shown that the combination of high BMI and daibetes type 2, is a much stronger predictor of mortality than elevated BMI alone, and therefore, DM2 should be weighted more heavily as a factor in determining eligibility for bariatric procedures. In addition, many patients who undergo bariatric procedures experience marked improvements in overall quality of life, with greater mobility, reduction of depression, and elimination of comorbid conditions, and a model capable of calculating the overall benefit of each type of bariatric procedure for prospective patients, including increased lifespan, rather than just reduction in the chance of premature mortality, may be a more useful approach. The acronym “QUALYS”, for “Quality Adjusted Life Years” has been coined as product of such benefit calculations.

Obesity – Bariatric Surgery options

Roux-en-y gastric bypass

The Roux-En-Y gastric bypass is the most performed bariatric surgery in the United States, accounting for 47% of all such procedures. It consists of dividing the stomach into two portions, a small pouch at the bottom of the esophagus and the rest of the stomach. Both portions are sealed off, and then the small intestine is attached to the small pouch. When food is ingested, it moves through the small pouch of stomach, and directly into the small intestine. Please click here to see an animation of the Roux-En-Y procedure. There are 2 apparent effects from this “rerouting”. Removal of the main body of the stomach from the flow of food reduces feelings of hunger, and leads to faster attainment of satiety (feeling of fullness). In addition, the food moves much more rapidly through the intestinal system, resulting in decreased absorption of nutrients and and, therefore, calories.

The Roux-En-Y procedure is irreversible.

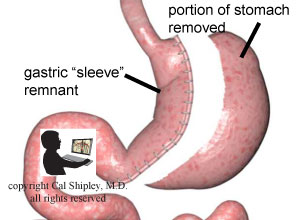

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy is currently the second most performed bariatric procedure, comprising 28% of bariatric procedures. The surgery consists of removal of a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, resulting in a tube-like remnant, or “sleeve” of stomach, markedly reducing the volume of food that can be ingested, and hastening satiety. Like the Roux-En-Y bypass, Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy is irreversible.

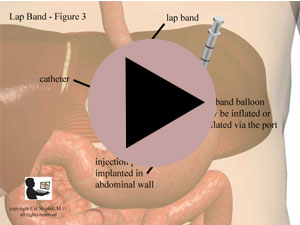

Adjustable Gastric Banding (Lap Band)

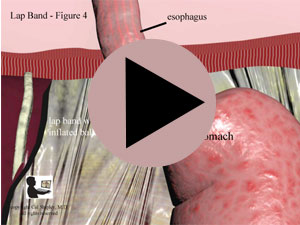

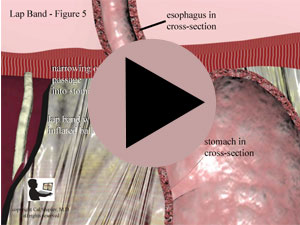

As of 2014, Adjustable gastric banding comprised 18% of bariatric procedures in the US. The procedure involves application of a band-like device (or “lap band”) around the very top of the stomach, just before the junction between the stomach and the esophagus. The device consists of a plastic collar, with an inflatable balloon attached to its inner side. (See illustrations below). After placement around the stomach, the surgeon inflates the balloon with saline. This has the effect of narrowing the channel through which food passes when it first enters the stomach. Movement and quantity of food that can be ingested over a period of time are markedly reduced, and satiety is apparently hastened. One of the big advantages of Adjustable Gastric Banding, unlike the Roux-En-Y or Vertical Gastric Sleeve procedures, is that it does not involve any irreversible changes to the stomach or intestinal tract. Moreover, an accessible port, with a catheter attached, is implanted in the abdominal wall. Via the port, saline may be added, or removed, as desired, inflating or deflating the balloon, thereby adjusting the width of the food channel, and increasing or decreasing the rate of weight loss.

Because of this ability to inflate or deflate the balloon, the Lap Band is completely reversible.

Obesity – Bariatric Surgery Results

While short term (2 years or less) weight loss benefit data is impressive, there is a relative lack of studies looking at long-term effectiveness and possible side-effects. One such study by Sjostrom et al, and an accompanying editorial by Solomon and Dluhy, both published in the New England Journal of Medicine in the December 23rd 2004 issue, did examine weight loss benefits at 2 and 10 years after surgery. The group they studied had all undergone surgery by the traditional criteria discussed earlier, that is, a BMI of 40 or greater, or a BMI of 35-40 with at least one metabolic “co-morbitiy” – ie – hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes mellitus type 2. They found that average weight loss 2 years post-procedure was 23 percent, and 16 percent at 10 years, while 1 percent and 2 percent of individuals had actually gained weight after 2 and 10 years, respectively. So on average, most patients who lost weight 2 years postoperatively, gained some of it back by 10 years, but were still well below their pre-surgical weight.

UPDATE Feb. 2017 – Here’s a recent study published in JAMA in November 2016, and authored by Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD et. al. which indicates sustained weight loss in bariatric surgery patients 10 years post-operatively, with better results for roux-en-y procedures compared to lap band or sleeve gastrectomy.

In addition, the researchers found improvement in obesity-related metabolic effects. Improvements were seen across the board in hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus type 2, ten years post-procedure, compare to a control group who had not undergone a bariatric procedure. What has not yet been established is whether myocardial infarction (heart attack), stroke, and death are significantly reduced in bariatric surgery patients.

On the downside, in the short term, post operative complications such as bleeding, infections and thromboembolism (abnormal clot formation) occur in about 13% of patients. There continues to be a lack of evidence on the potential for long-term side effects with bariatric surgery. Long term complications such as stomal stenosis (abnormal narrowing and obstruction of stomach or intestines), anastomotic ulcers (tissue breakdown where the stomach and intestines are surgically joined), and nutritional deficiencies, have been reported, but solid data remains scarce as of this writing.

Obesity – Vagus Nerve Blockade – a new Bariatric procedure

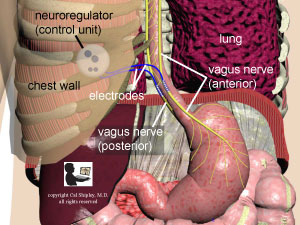

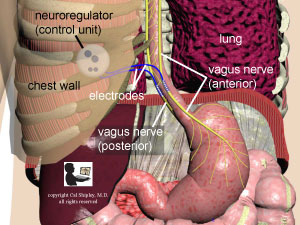

The vagus nerve has long been known to affect metabolism, satiety (feeling of fullness) and upper gastrointestinal tract function. Recent research has shown that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve, resulting in an interruption of the normal signals transmitted along the nerve (blockade) may result in alterations in satiety and subsequent weight loss. A recent study of vagus nerve blockade by Ikramuddin et al (the ReCharge trial), published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, took a closer look at this new procedure.

The vagal blockade procedure involves the placement of electrodes on both the anterior and posterior vagus nerves by means of a minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure through the abdomen. The electrodes are connected to a small “neuroregulator” device which is implanted subcutaneously into the chest (thoracic) wall. In the Ikramuddin study, the vagus nerves were blockaded for 12 hours a day.

The “goal” of the study was a loss of 25% of the excess weight of participants. This goal was not achieved, although weight loss observed in participants was statistically significant compared to a control group who were implanted with a “sham” device. The vagus nerve blockade procedure did have a very low rate of serious complications. The authors concluded that further research into this procedure is needed before it can be recommended as a reliable means of weight loss in the obese.

Obesity treatment – Medications

Medications are by far my least favorite of the treatments for obesity. They are fraught with possible side-effects, they cannot be safely taken over the long-term, and they teach patients nothing about the lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, etc.) that are critical to healthy long-term weight loss and maintenance. In short, they are a “quick fix” of the worst sort. Here is a quick review based on a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Orlistat – is a lipase inhibitor, and works by blocking absorption of fats from the gut. It commonly causes excessive flatulence, oily staining and fecal urgency, and its use among obese Americans is limited.

Sympathomimetic Amines – such as methamphetamine, are still approved by the FDA for weight loss. They are addictive, and stress the cardiovascular system with increased heart rate and blood pressure (through stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system), and are currently in very limited use.

Lorcaserin – is a serotonin 2C receptor agonist (stimulant), and appears to suppress appetite without the dangerous adverse effects of other serotonin receptor subtypes (hallucinations, cardiac valvulopathy (heart valve damage), and pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the blood vessels of the lung). However, other adverse effects such as headaches, dizziness and nausea have led to high discontinuation rates among users in 3 different studies.

Phentermine/Topiramate (Qsymia) – is a combination of 2 drugs. Phentermine is a sympathomimetic amine that was formerly joined with another SA, fenfluramine with disastrous results. The combination drug caused serious cardiac valvular disease in many patients, apparently mostly as a result of the fenfluramine component. Fenfluramine was withdrawn from the market in 1997. Topiramate is approved by the FDA for use treating migraine headaches and seizure disorders. It has produced weight loss in some studies, but the mechanism is unknown. The side effects associated with the phentermine/topiramate combination have been significant, and include dry mouth, paresthesia, constipation, alteration in taste perception, insomnia, and cognitive difficulties affecting attention, concentration and memory. Topiramate is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor and can cause metabolic acidosis and kidney stones. Anti-epileptic drugs have also been associated with suicidal ideation and behavior.

Obesity – Bottom Line

The obesity plague rolls on, and America continues to both struggle with its enormous costs (both medical and societal), and, ironically, in some sectors, profit from it. It seems that the problem will never have a significant resolution until fundamental attitudes towards food, and the manner in which it is promoted, packaged, and delivered to us, undergoes radical change. As long as salt, fat and sugar are revered as the “Holy Trinity” of food, and can be obtained more cheaply than higher quality alternatives (preferably low-fat and organic), the plague will continue…

*the definition of serious varies from organization to organization, but generally refers to at least one or more of the following: 1) dietary counseling and intervention of at least 12 months duration in association with regular exercise 2) psycho-social evaluations and 3) collaboration and recommendation by the patient’s primary care physician and bariatric surgeon that the benefits of proceeding with the procedure outweighs the risks.Back to Bariatric Surgical Treatment

Cal Shipley, M.D. copyright 2021